Lecture Notes of Week 1: System Earth and the Challenge of Sustainable Development

notes compiled by Dr. S. de Meer

1. The Planet Today

The Earth as it appears today is a both chemically and physically layered body.

Chemical layering:

| Composition | Thickness (km) | |

| Crust | O, Si | 0 - 40 |

| Mantle | O, Si, Fe, Mg | 40 - 2891 |

| Core | Fe, Ni | 2891 - 6370 |

Physical layering:

| Material / properties | Thickness (km) | |

| Lithosphere | cool, hard rock | 50 - 100 |

| Asthenosphere | weak, soft rock | 150 - 200 |

| Mesosphere (lower mantle) | dense, rigid rock | ~2700 |

| Outer Core | liquid iron and nickel | ~2100 |

| Inner Core | solid iron and nickel | ~1300 |

2. The Earth's component systems:

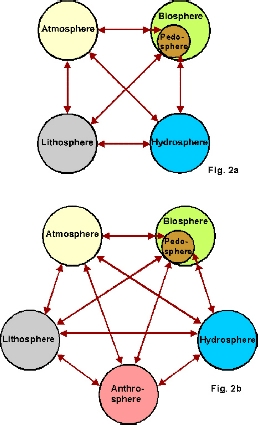

In the "Earth Systems" course, you were introduced to (see Fig. 2a):

- Lithosphere

- Biosphere (+Pedosphere)

- Atmosphere

- Hydrosphere

Here, we will introduce another system, the anthrosphere or humankind (Fig. 2b). We will look at how the Earth systems influence humankind and, vice versa, how humankind interact with and have caused changes to occur in the Earth systems. Before we go into these interactions between the Earth and humankind, we will shortly recapitulate some of the topics dealt with in your "Earth Systems" courses.

3. Plate tectonics

According to the theory of plate tectonics, the Earth's lithosphere is broken-up into several larger and smaller rigid plates (Fig. 3) that are in motion over the Earth's surface.

Figure 3. The most important lithospheric plates.

The plates constantly move around on the underlying "hot, weak" asthenosphere. Because the Earth's interior is still hot, and even though the mantle beneath the lithosphere is mostly solid, it is ductile or moldable. It can flow or "creep" driven by convection forces. It are these large convection cells within the Earth's mantle that drag the overlying plates along (Fig. 4). The movement of plates is at a rate of a few centimeters per year.

Figure 4. Cartoon of the basic plate tectonic processes.

The plates are bordered by divergent, convergent, and transform fault boundaries (see Fig. 5).

3.1. Divergent plate boundaries , are plate boundaries where plates seperate and move in opposite directions, allowing new lithosphere to form from upwelling magma.

- Also called Mid-ocean ridge or seafloor spreading ridge (within oceanic crust)

- Also called rift-zone (within continental crust)

- Marked by submarine volcanism and frequent but weak earthquakes

- Examples: East Pacific Rise, Mid-Atlantic Ridge

3.2. Convergent plate boundaries , are plate boundaries where plates collide and one sinks beneath the other, returning existing lithosphere to the earth's interior (Figs. 6a-c).

- Also called subduction zones or collision zones

- Marked by explosive volcanism and powerful earthquakes

- Examples:

- Aleutian Trench Japan Trench, (oceanic-oceanic convergence)

- Peru-Chili Trench (oceanic-continental convergence)

- Tibetan Plateau (continental-continental convergence)

3.3. Transform fault boundaries , are plate boundaries where plates slide past each other, approximately at right angles to their divergent boundaries (Fig. 7).

- Frequent sites of powerful earthquakes, but no volcanism

- Examples San Andreas Fault (Fig. 7)

The theory of plate tectonics has been the greatest revolution in the Geosciences, When it was proposed in the 1960's it caused an enormous shock amongst geologists. For a long time geologists supported various theories of mountain building, volcanism and other major phenomena of Earth, but no theory was sufficiently general to explain the whole range of geological processes. Plate tectonics is a unifying theory in that it explains all Earth's major geological features, like for example the classification and distribution of rocks and the positions and characteristics of volcanoes, earthquake belts, mountain systems, and ocean basins. The plate tectonic picture as it is outlined above is very much simplified and a large number of details have been left out. To learn more about plate tectonics, visit the Websites mentioned in the course manual or go directly to "Useful WebSites".

4. Internal and External Energy Resources

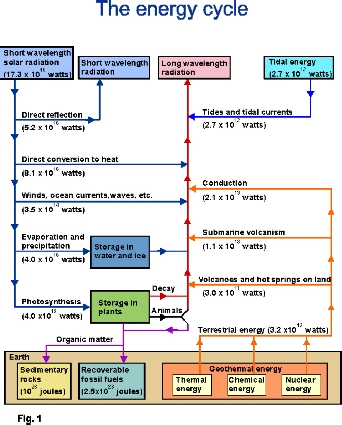

The greatest source of energy at the Earth's surface is short wavelength radiation from the sun (Fig. 8). This external energy source provides an inflow of 173,000,000,000,000,000 W, or 173,000 TW (terawatts), per year and makes up 99.98 percent of the energy flow on Earth. Solar energy is the ultimate origin of nearly all other energy sources on Earth, including the energy stored in wood, coal, oil, natural gas, falling water, and wind.

Figure 8. Earth's energy cycle.

The Earth's internal heat, which supplies only 32 TW a year to the surface, is responsible for driving the processes of volcanism and plate tectonics. Earth's internal heat energy also can turn groundwater to steam, producing geysers and geothermal fields.

Gravitational attractions among Earth, Moon, Sun, and other bodies in the solar system supply a mere 2.7 TW a year of potential and kinetic energy (tidal energy). Nevertheless, this small source of energy causes both ocean and Earth's crust to change shape with time in a regular fashion, resulting in ocean and rock tides.

Extracting and burning fossil fuels releases stored energy that originated as sunlight and was used by organisms for photosynthesis long ago. Although the rate at which solar energy becomes stored in fossil fuels is small, it has accumulated in the lithosphere over periods of millions to hundreds of millions of years, and so the total stock of fossil fuel is very large.

The modern world currently relies on nonrenewable fossil fuels for more than 75 percent of its primary energy needs (for heating and electricity). Renewable biomass and hydroelectricity supply most of the rest. Nuclear power accounts for only 4 percent of energy use. Although the uranium oxides from which nuclear power is derived contain the largest stock of nonrenewable energy on Earth, the risks of radiation exposure inhibit the development of the energy resource. Geothermal energy from the Earth's interior heat flow is essentially a perpetual resource at a few locations but is insignificant in the world energy tally. Direct solar energy and wind energy are perpetually available and environmentally benign but are little used. The origin, economic potential, and environmental effects of fossil fuels will be discussed at a later stage during the course.

5. Interactions and Feedback between Earth systems

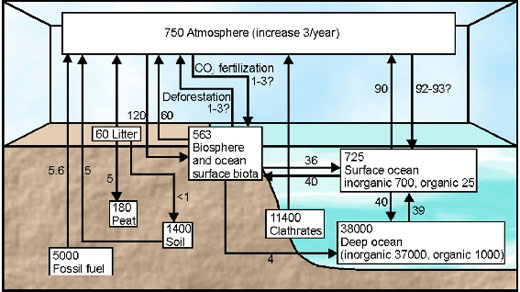

Interdependent environmental systems are characterized not only by feedback mechanisms but also by the circulation of matter and energy (see Fig. 8) in endless loops or cycles. Nearly all matter on Earth is recycled over and over again. For example, when fossil fuel is burned in an automobile, its carbon is released into the atmosphere. From there, the carbon might be extracted by trees during photosynthesis, and from them it might be returned to the atmosphere, or buried in sediment to become a fossil fuel yet again. This important cycle - the carbon cycle (Fig. 9) - will be discussed in detail during a later stage in the course.

Figure 9. Box model for the global carbon cycle. Each box represents a different reservoir; the numbers indicate the mass of carbon, in billions of metric tons, in that reservoir. Arrows and numbers between boxes represent exchanges (flows and fluxes) of carbon in billions of metric tons per year.

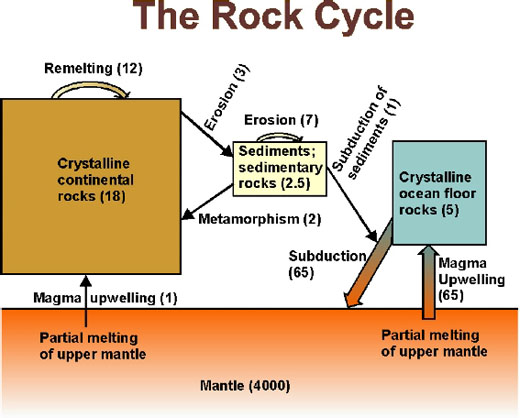

5.1. The Rock Cycle (cycling of solid material)

In terms of a human life span, rock seems eternal. For example, mountains seem fixed to many people, yet to the geologist they are evidence that young rocks have been pushed upward by plate tectonics processes. The continual creation, destruction, and recycling of rock into different forms is known as the rock cycle (Fig. 10), and it is driven by plate tetonics, solar energy, and gravity. The rock cycle begins when tectonic forces drive molten rock from the Earth's mantle toward the surface. The hot melt is less dense than the surrounding, cooler mantle rock and rises buoyantly through it. As the hot melt rises, it cools and freezes into igneous rock. water wind, biological activity, and other environmental stresses may weather the rock, dissolving and breaking it up into particles that eventually move downward and accumulate in layers of sediment. Under sufficient pressure, sediments harden into sedimentary rock. Alternatively, tectonic forces either may drive sedimentary and other types of rock back into the mantle and remelt it into magma, or subject the rock to enough heat and pressure to transfer it, without melting, into metamorphic rock. All rocks on Earth can be classified as igneous, sedimentary, or metamorphic.

Figure 10. The rock cycle portrayed as a system containing four major reservoirs (rectangles) and the flows, or fluxes (arrows), of matter among them. The masses of the reservoirs are expressed in units of exatons (ten to the eighteenth tons). Flow rates are expressed in units of gigatons per year. Boxes and arrows are drawn in relative scale. Note that the mantle reservoir is so large that it can not be shown in its entirety.

5.2. The Hydrological cycle (cycling of liquid material)

Unlike rock, which changes physical and chemical state and location over long periods of geological time, large volumes of water change physical state and location over relatively short periods. The movement of water from one reservoir to another is the hydrological cycle (Fig. 11), and it is the fundamental, unifying concept in the study of water on Earth.

Figure 11. The simplest model of the hydrological cycle shows the flux of water through evaporation from oceans to precipitation on continents and back again to oceans through runoff. Other processes involved in the movement of water are transpiration (the release of water vapour by plant and animal cells) and percolation of water below the ground surface along openings such as pore space in sediments or fractures in rocks. In this zone, water flows as groundwater toward areas of low elevation and pressure, such as streams and springs. Eventually, this water, too, will return to the atmosphere or ocean and continue the cycle.

5.3. The Nitrogen Cycle (cycling of chemical component)

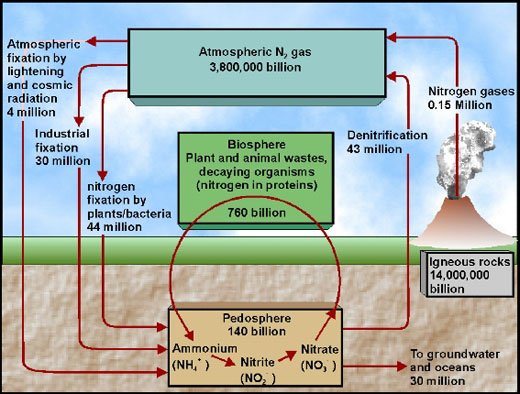

The nitrogen cycle (Fig. 12), the continuous flow of nitrogen through the atmosphere, biosphere and pedosphere, is as essential to life as are the carbon and hydrological cycles. Because nitrogen is a key ingredient in proteins, DNA and RNA, life is limited by the amount of available nitrogen. Although nitrogen is the most abundant element in the atmosphere (79 percent by volume), it is an inert gas, and only a few organisms are able to use it directly. A few types of soil bacteria are able to fix atmospheric nitrogen. Usually they live symbiotically with higher plants feeding off the sugars made by plant, while breaking apart nitrogen molecules for plant use. As organisms die, their protein molecules and the nitrogen they contain become available to other soil microbes who convert this to ammonium, nitrite and nitrate, all of which are usable plant nutrients. A part of these nutrients is taken up by groundwater and flows to the ocean, while another part is recycled to the atmosphere by denitrification (conversion of organic nitrates into gaseous nitrogen).

Figure 12. The nitrogen cycle - with stocks and flows - for continental land areas. Rates of annual flow are indicated by the arrows, and the stocks as rectangular boxes. Flow rates are in millions of metric tons per year and stocks are in billions of metric tons.

Humans are altering the nitrogen cycle in two important ways. The first is increasing cultivation of nitrogen-fixing vegetables throughout the world. The second, known as industrial fixation, is the use of fossil fuels to produce nitrogen in the form of synthetic fertilizers. Nitrogen fixation now greatly exceeds denitrification. Since the development of agriculture, nitrogen fixation has increased by as much as 10 per cent. A direct result of increased nitrogen fixation has been the increased discharge of nitrogen into streams and rivers, loading them with extra nitrogen. In many bodies of water, the excessive supply of nitrogen and other fertilizers in nutrient form intensifies biological activity and can produce algae blooms. When algae and other plants die and settle to the bottoms of lakes and bays, the organisms that decompose them consume oxygen, depleting it from the water. This overall process of nutrient-induced oxygen depletion is known as eutrophication and has been blamed for the death of many fish in aquatic environments.

6. Geological time and the Geological Record

Knowing the age of geological events can be crucial to life on Earth. Consider the problem of radioactive waste disposal. Exposure to radioactive emissions damages living cells. Therefore, nuclear waste has to be stored in closed containers for periods up to 100,000 years before radioactive emissions are within safety limits again. The international community is studying the possibility of permanent radwaste disposal sites within solid rock several hundreds of meters beneath the Earth's surface (see also Part 2: Non Fossil Fuels Energy Resources and the Utilization of Underground Space). Scientists must determine whether or not the facility will remain intact and safe from disturbance and migration of wastes for periods up to 100,000 years. Clearly, the major technological risk is the challenge of time: No known human engineering works have survived this long. The meaning of a 100,000 year time span is hard to grasp when the human lifetime is only 70 to 80 years, and geological time, which is measured in spans of hundreds of thousends to billions of years, may seem beyond comprehension. Nevertheless, an understanding of the time scales and the space scales of earth's processes is vital to predicting geological hazards and using resources wisely. Consider our dependence on a finite store of fossil fuels such as petroleum. The rich store of oil in the Earth's crust took millions of years to form and are distributed in rock formations that extend over distances of tens to hundreds of kilometers. They could be depleted, however, in a matter of decades at our current consumption rates.

Geoscientists assume that the causes of past events can be used to predict future events. This assumption comes from the fundamental premise that processes occurring on Earth today are the same as those that occurred in the past; known as the principle of uniformitarianism. Uniformitarianism does not imply that the rates of all processes remain exactly the same with time. Rather it means that processes observed today can be used to explain events that occurred earlier in Earth's history because the physical laws that control these processes remain constant. For example, by emitting large volumes of particulate matter and gases into the atmosphere, Mount Pinatubo's eruption in the Philippines in 1991 affected global climate for several years thereafter. Similar but older volcanic deposits occur in the surroundings of the mountain. Using the principle of uniformitarianism, Earth scientists infer that the volcano has erupted repeatedly over the past few thousends of years and, furthermore, that past large eruptions might also have affected global climate. The idea that "the present is the key to the past" can be extended to predict what might happen in the future. By interpreting the geological record, it helped scientists to predict the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens (Washington, US). Similar reasoning is the basis for the intense scrutiny of rocks and sediments at the proposed nuclear waste site at Yucca Mountain (Nevada, US).

6.1. Relative Geological time

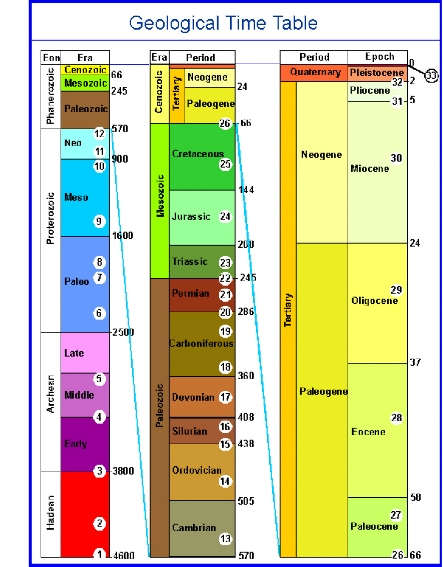

As new ways to determine rock ages were developed in the past few centuries, the estimated age of Earth increased many orders of magnitude. In the 17th century, Earth was thought to be about 6000 years old. Today, it is considered to be about 4.6 billion years old, about 700,000 times the earlier time estimates. The age estimates changed as new scientific understanding and technologies enabled greater accuracy and precision in dating rocks and geological events. Was the age of the Earth first established from tracing genealogical evidence in the Bible, early scientists observed the Earth's rocks for clues to the Earth's age. Two people stand out as having ideas far ahead of those of their contemporaries, Leonardo da Vinci and Niels Stensen (Nicolaus Steno). Leonardo da Vinci studied layers of sand, gravel and fossil debris in central Italy. He concluded that the fossils could not have travelled as far and as high up into the mountains during the 40 day biblical flood, but that the fossils were remains of animals that once lived on the seafloor, and that the land had been raised since then. His hypothesis was strengthened by the groundmotion and regular occurrence of earthquakes in central Italy, which he related to uplift of the rock. Niels Stensen formulated two laws for the formation of rocks. The first law, the principle of superposition explains the sequence of events leading from the settling of particles at the bottom of a column of water, to the formation of strata (layers of rock) by compression. Steno realized that in a sequence of strata, a given stratum is younger than those below it and older than those above it, hence the term superposition. The second law, related to the first, is the principle of original horizontality : strata are originally deposited in uniform, horizontal sheets. Because of plate tectonics and mountain building processes that deform rocks, strata often become tilted and folded. Using the laws of Steno, a relative geological time scale (Fig. 13) was developed based entirely on stratigraphy and fossils. Absolute ages could only be put to the geological time scale after the discovery of radioactivity.

Figure 13. Geological time table showing the Eons, Eras, Periods and Epochs of the Earth's history. The vertical scale is in millions of years ago from present. Numbers correlate to major events in the Earth's history and are listed below.

- 1. Origin of the Earth

- 2. Magma ocean; hydrosphere and atmosphere form as gases escape from the Earth's interior

- 3. Oldest known rocks

- 4. Earliest life-forms (single-celled bacteria)

- 5. First algae (blue-green) and photosynthetic bacteria

- 6. First ice-age - glaciers on all continents but South America; formation of large continents

- 7. Oxygen builds up in atmosphere; multicelled life-forms in ocean

- 8. Mountain building

- 9. Mountain building

- 10. Mountain building; oxygen-dependent life-forms in ocean

- 11. Second ice-age

- 12. Proliferation of multicelled life-forms in ocean; first Jellyfish

- 13. Marine animals (invertebrates) with shells abundant; Trilobites dominant

- 14. Antarctica located near equator; glaciation in nothern Africa; first Brachiopods and Starfish

- 15. Third ice-age

- 16. Coral reef formation; first land plants

- 17. Mountain building in NW Europe and NE America; first forests; fish abundant in ocean; first amphibians

- 18. Large primitive trees

- 19. First period of coal formation; abundant insects; first reptiles

- 20. Fourth ice-age

- 21. Mountain building in Europe; formation of Appalachians; expansion of reptiles

- 22. Mass extinction (Trilobites and many more marine animals)

- 23. Formation of Pangea (single continent); first dinosaurs; ferns flourish

- 24. Pangea breaks up; age of dinosaurs; first birds and mammals; conifers flourish; deserts widespread

- 25. India splits from Antarctica; second period of coal formation; first primates and flowering plants; insects flourish

- 26. Mass extinction (dinosaurs and many other species)

- 27. Formation of Rocky Mountains; first true birds; flowering plants dominant on land

- 28. Seperation of Antarctica from Australasia; linking of Afrika and Eurasia; first horse; insects and birds flourish

- 29. Collison of India with Eurasia; first whales and monkeys

- 30. Formation of Alpine and Himalayan mountains; first mammals with claws

- 31. Global cooling; evolution of human species

- 32. Fifth ice-age (continuing until today)

- 33. Last 10,000 years usually referred to as Holocene; rapid human population growth and development of agriculture

The first three Eons in the history of the Earth (Hadean, Archean and Proterozoic) are often referred to together as Precambrian.

| Era / Period(s) | Also known as |

| Cambrium + Ordovician | Age of Invertebrates |

| Silurian + Devonian | Age of Fishes |

| Carboniferous + Permian | Age of Amphibians |

| Mesozoic | Age of Reptiles |

| Cenozoic - Holocene | Age of Mammals |

| Holocene | Age of Humans |

Table 1. Different names for certain periods in geological time

6.2. Absolute Geological Time

An unstable atom (parent) decays spontaneously, losing particles and energy from its nucleus, and becomes another element (daughter). The number of radioactive atoms that decay in a given period of time is proportional to the number of radioactive atoms in the sample, half will decay over a constant period of time. The use of radioactive decay processes to date rocks and organic matter is known as radiometric dating. Radiometric dating requires certain information to be useful; in particular, one must know how much of the parent isotope was originally present in a substance at the time of its formation. To date a sample of a mineral or organic matter using a given isotope, the amounts of daughter and remaining parent isotopes are measured, then the duration of time that radioactive decay has been occurring is calculated. For most unstable isotopes, their use in radiometric dating diminishes after about 10 to 15 half-lives because the number of parent atoms remaining becomes too small to detect. The longer the half-life, the older the sample that can be dated (see Table 2).

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Parent | Daugther | |||

| Samarium-147 | Neodymium-143 | 105 billion | 300 million - 4.6 billion | Mafic and ultramafic rocks |

| Rubidium-87 | Strontium-87 | 47 billion | 10 million - 4.6 billion | Muscovite, biotite, Potassium feldspar, whole metamorphic or igneous rock |

| Uranium-238 | Lead-206 | 4.5 billion | 10 million - 4.6 billion | Zircon, Uranite |

| Potassium-40 | Argon-40 | 1.3 billion | 50,000 - 4.6 billion | Muscovite, biotite, hornblende, whole volcanic rock |

| Carbon-14 | Nitrogen-14 | 5730 | 100 - 70,000 | Wood, charcoal, peat, bone and tissue, shell and other calcium carbonate, groundwater, ocean water and glacier ice containing dissolved carbon dioxide |

Table 2. Major radioactive elements used in radiometric dating, dating ranges and applications.

Processes and events of past ages are inferred from stratigraphy, not from radiometric dating, but the two can be combined to provide a fuller picture of Earth history. Earlier it was shown that layered sedimentary rocks containing fossils enabled geologists to develop a geological column in which rocks are arranged in chronological order relative to one another. Geologists combine relative stratigraphic ages with radiometric dating by studying localities where molten rock has intruded or buried a sequence of strata. The intrusions and flows, which can be radiometrically dated, are used to bracket the ages of the sedimentary strata above and below them.

7. Evolution of the Earth and Life on Earth (Paleoenvironment and Paleoclimate)

The whole dynamic Earth system is powered partly by the planet's own internal energy but mostly by energy from the sun. Earth's internal and environmental systems are rooted in the way the planet evolved within our solar system, which itself evolved within the univers. Years of research by astronomers and physicists have produced a widely accepted theory of the origin of the univers, stars, and planets. Properly called the Cosmic Singularity Theory, it is commonly referred to as the theory of the "Big Bang". According to the Big Bang theory, some 10 to 20 billion years ago an explosive cosmic event occurred from which all energy and matter are derived. Unimaginably hot, pure energy in the form of gamma rays filled the univers, cooling as it expanded and decaying to form subatomic particles of matter (Einstein's E=Mc2), which combined to form Hydrogen and Helium. Gravity drew the hydrogen and helium together, condensing them and thereby heating them into glowing gas clouds from which galaxies were born. Within galaxies, dust and gas continuously gravitate into nebulae. Our solar system evolved from such a nebula. The nebular hypothesis of the origen of solar systems holds that nebulae condense to become stars, and planets are created as a by-product of star formation. Gravitational attraction draws the matter in a slowly rotating nebula into a flattened whirling disk, with the bulk of the matter at the center, where it develops into a star. Around the central star, the remaining materials in the nebula gravitate into larger bits of rock and metal that coalesce into planets orbiting the star. Our solar system is believed to have formed this way about 4.6 billion years ago.

During the first half-billions years of Earth history, so much debris was present in the solar system that Earth was bombarded by meteors left over from the period of planet formation. As the Sun became luminous, its radiation created solar winds, which forced much of the remaining debris out of the solar system. Since then, Earth's mass has remained essentially static. Soon after the Earth had formed from accreting debris, it began to heat up as a result of collision of debris, compression of debris and radioactive decay of chemical elements. This led to a period of complete or nearly complete melting and resultant segregation of the Earth's elements into chemically distinct layers; core, mantle and crust. Temperature and pressure also caused the Earth to form a distinctive physical layering (see also the lecture notes of the corresponding exercise).

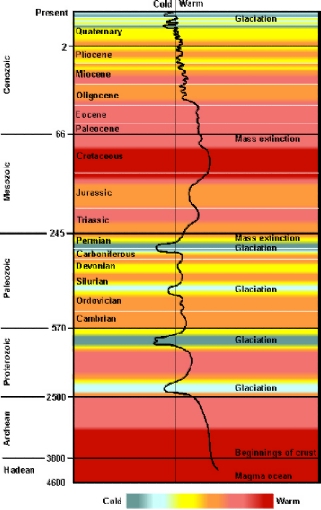

The Earth has undergone dramatic changes throughout its history. The conditions that surround us today are the result of those changes, and the future is governed by the same physical principles that governed the past. Foremost among the factors that have influenced our planet is temperature. Variation in global temperature (Fig. 2) have been controlled by numerous influences, each of which has been dominant in the past. These influences include the Earth's orbital parameters (recall Milankovitch Cycles - System Earth Course), Earth's internal temperature, the evolution of plants, the configuration of continents, and sudden catastrophic disturbances (e.g. meteorite impacts, volcanic eruptions).

Figure 14. Earth's climate during its entire history.

For the first few hundred million years, Earth probably was a "magma ocean", a boiling ball of molten rock. The high heat flux came from the kinetic energy of earth's accretion, the radioactive decay of elements, and from the gravitational energy associated with the differentiation of the Earth into layers. By the end of the Hadean eon, the Earth's crust had begun to solidify and differentiate into dense, iron-rich basaltic rock that formed the ocean basins and lighter, more siliceous rock that rose buoyantly above the denser basaltic rock to become continental landmasses. As plate tectonics developed, heat and gases (carbon dioxide and water vapour) escaped from Earth's mantle. Sediments from this age suggests the presence of a hydrosphere.

In the Archean eon, the Earth's surface was dotted with microcontinents seperated by great expanses of shallow oceans. By that time the planet's surface was cool enough for single-celled blue-green algae to develop. As the Earth cooled, radiation from the sun was much less intense than it is today. If the powerful greenhouse effect of the abundant carbon dioxide had not counterbalanced the low amounts of incoming solar energy, the Earth would have frozen.

In the early Proterozoic eon (2.3 billion years ago), the first large glaciation developed on Earth. The cooling might be attributed to the continued low luminosity of the early Sun combined with a weakened greenhouse effect on Earth as photosynthetic marine plants flourished and removed carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. From 2.3 billion to 900 million years ago, temperatures appear to have climbed for reasons not yet understood. Between 900 and 600 million years ago a second ice-age occurred which has also been attributed to a decreased solar luminosity and a weakened greenhouse effect.

With the beginning of the Phanerozoic eon (in which we still live today), plate tectonics began to dominate climate changes. When a particular landmass moved to a new position on the globe, its climate and environment also changed. Paleomagnetism has made it possible to determine whether an ancient continent was previously located at the equator, at a pole, or somewhere in between. The Paleozoic era was a time of great supercontinents. paleomagnetic evidence tells us that most of the land in the Paleozoic era was located in the equatorial and low latitudes. Therefore, the terrestrial climate was mild, except for two episodes of glaciation that began at approximately 440 million and 305 million years ago (the last only on the southern continent "Gondwanaland") and probably stemmed from continental drift toward the poles. Directly after the first glaciation the first landplants evolved in the Silurian period (see also Fig. 1) and were folowed by the first amphibians around 360 million years ago during the late Devonian period (suggesting a warm climate). Warmth and wetness continued up to 286 million years ago, and swamps covered much of what would become North America and Europe. Some of the plant matter ultimately was transformed into coal and gave the Carboniferous period its name.

By the early Triassic period, all the continents on the globe had collided to form the supercontinent Pangea. The growth of Pangea was accompanied by major changes in regional environments and life-forms. Mass extinctions occurred and other life-forms evolved. Dinosaurs came to prominence at this time. In the middle Triassic, Pangea began breaking up and the beginning of the Atlantic ocean formed in the rift zone between the landmasses that became Europe and North America. Rifting continued until the Cretaceous period, when North America finally pulled completely away from Europe and Africa. Plate tectonics influences the Earth's environments not only by determining global geography, but also through rates of tectonic processes. The Cretaceous period was marked by very high temperatures, attributed to an increase in sea-floor spreading rates and accompanying increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration (greenhouse effect) as volcanic gases issued from the spreading centers.

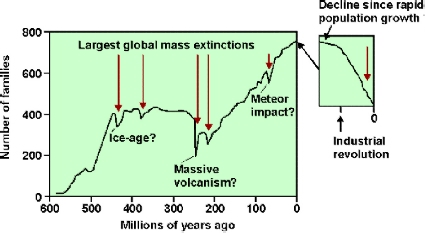

The Cretaceous period and Mesozoic era ended with a cataclysmic event that brought about the exinction of dinosaurs and the ascendency of mammals. The cause of the extinction (in which more than 50 per cent of existing species perished - see also Fig. 3.) has been hotly debated for decades. One possibility is that the massive volcanism that created flood basalts in India at the time disturbed the environment enough to cause mass extinctions. However, the evidence now weighs in favour of the hypothesis that a huge meteorite or cluster of meteorites hit the Earth 65 million years ago. (/p>

Figure 15. Fluctuation in the estimated number of families (groups of related species) of marine organisms. Arrows point to the five largest global mass extinctions. The general trend has been towards greater biological diversity until present, but a sixth major decrease in number of species is occurring now, as a result of human activity. The strong increase in species since ~200 million years ago is generally believed to be a result of the break-up of Pangea, it created diverse new environments, including extensive nearshore areas that provide rich habitats.

A buried impact crater 65 million years old has been identified offshore Mexico's Yucatan pennisula. An impact powerful enough to gouge out such a crater would have vapourized the meteorite into a dust that would eventually settle in layers around the globe. Indeed, at sites throughout the world, a clay layer of that age has been found containing unusually high quantities of iridium, an element common in certain types of meteorites, but very rare in earth materials. North of the crater, in North America and southern Europe, some iridium-rich sites also contain impact-metomorphosed quartz grains that are found only in connection with meteorite impacts and nuclear explosions. Large quantities of carbon, suggestive of global wildfires, are also present.

Following the Cretaceous, the Cenozoic era remained quite warm for its first 27 million years or so. Why the global climate remained so warm in the Eocene epoch, long after accelerated seafloor spreading in the Cretaceous period had slowed and after the warming seas had receded, remains a mystery. In the Eocene epoch, however, there began a sequence of one-way geographical and biological changes that mark the onset of a prolonged trend in global cooling during the Cenozoic era. After the Eocene epoch, the rate of Cenozoic cooling changed from time to time, but the overall trend contiued, favouring the rise of mammals, and driving the Earth into the last great ice age.

8. Accumulation of Resources

Mineral deposits or not randomly ditributed in the Earth. They are a direct product of their geological environment and of the time in Earth's history at which they were formed (Fig. 16).

Figure 16. Formation of important types of mineral deposits through geological time.

Ore-forming processes are closely related to plate tectonic activity. In the ocean crust, seawater hydrothermal systems are formed along the mid-ocean ridges by the heat of rising magmas. Magmatic processes beneath the ridge also generate cumulate deposits, altough such deposits are seen only in a few obduction zones. Most other ore-forming processes take place in continents. Meteoric hydrothermal systems are found at rift zones, where volcanism is abundant and magmas are near the surface. Magmatic hydrothermal systems are common above subduction zones, where felsic and intermediate magmatism is widespread, but are not as strongly developed along mid-ocean ridges, probably because basaltic magmas contain less dissolved water. Sedimentary basins and related waters, oil, and gas form along passive margins of continents, around volcanic arcs, and in rift zones. Some basins even form in the central parts of continents, possibly in response to the collapse of old rift zones in the underlying continent. Metamorphic waters are released wherever sedimentary or volcanic rocks undergo metamorphism, usually along collisional margins. Even ore-forming processes that take palce at the Earth's surface are affected by plate tectonics. Placer deposits form where mountains have been uplifted, largely along collisional margins. Evaporite and laterite deposits are related to plate tectonics because weather patterns are a function of the size of a continent and its position with respect to the poles.

Because of their close link to global geological processes, mineral deposits also reflect important changes in Earth history (Fig. 16). For instance, during Archean time, the upper mantle was hotter and partial melting took place at higher temperatures, extracting unusual ultramafic magmas that formed rocks known as komatiite. Komatiite magmas were rich in sulfur and nickel and formed immiscible magmatic sulfide magmas more readily than the basaltic magmas that come from the mantle today. Metamorphism and intrusion in volcanic arcs in Archean time apparently produced larger amounts of hydrothermal fluids as well. By late Archean and early Proterozoic time, sizeable continental masses had developed. Erosion of them produced a new geological environment consisting of large sedimentary basins with shallow shelf areas. Where these basins are preserved, they contain large chemical and clastic sedimentary deposits, including much of the Earth's iron, gold, and uranium ores. These deposits also reflect the changing composition of the atmosphere because they apparently did not form after middle Proterozoic time when oxygen content of the atmosphere became high enough to change the geochemical behaviour of iron and uranium at the surface. By Phanerozoic time, the continents had grown large enough to host even bigger sedimentary basins, which contained limestone and evaporite minerals. The appearance of marine organic life enhanced the probability of forming crude oil and natural gas and the appearance of vascular land plants enabled the formation of coals deposits. Hot brines expelled from these basins formed Mississippi Valley-type lead-zinc deposits, which are rare in pre-Phanerozoic rocks. The increased concentration of oxygen in the atmosphere permitted more effective dissolution of uranium during weathering of the rocks and allowed the creation of uranium deposits related to groundwater movement. Finally, numerous collision margin volcanic arcs developed on the newly formed continents, leading to the formation of mineral deposits associated with meteoric and magmatic hydrothermal systems.

9. The Ascent of Humans

After the extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, mammals flourished and evolved on Earth. Primates appeared in African forests during this time. Primates are an order of mammals that includes apes and humans. Between 2 and 4 million years ago the climate of tropical Africa became drier and warmer and forests shrank, possibly encouraging some early primates to walk upright into the encroaching savannas. A large-brained, upright-walking, talkative primate evolved in this grassland environment some 50,000 to 100,000 years ago. It was our own species, which we now call Homo Sapiens, for "thinking man". From about 25,000 to 12,000 years ago, human beings endured ice-age conditions. Ice sheets covered large parts of North America and Europe. With significant amounts of water bound in extensive ice sheets, sea level dropped, exposing land bridges between several continents. Using these land bridges, people migrated to previously unreachable lands. About 10,000 years ago global climate became generally warmer, and ice sheets in North America and Europe melted. Early in this period of relative warmth our ancestors discovered how to grow their own food crops and to domesticate animals. As the climate grew warmer and drier in many parts of the world, humans learned to divert stream water into irrigation ditches and to control the flow of water in reservoirs behind dams. With this Agricultural Revolution, more people could be supported in smaller areas than hunters and gatherers required, and the first cities arose about 7000 years ago. Accumulation of the world's people in increasingly larger cities continues to this day. In turn, the closer proximity of humans in urban areas spurred the transfer of ideas and new technologies. People became increasingly reliant on metals for toolmaking and on fuels such as wood for energy. The Industrial Revolution, which began in the 1700s, marks a time of significantly increased consumption of energy and production of manufactured goods. People discovered means of converting ancient solar energy stored in fossil fuels into mechanical energy, a large part of which is used now to grow and transport agricultural food products around the world.

10. Critical Issues for Sustainable Development

Population Growth

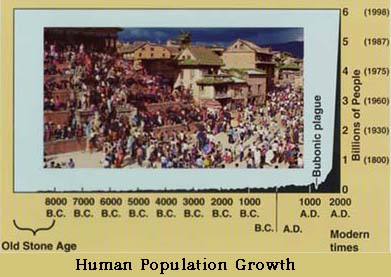

As a result of our growing ability and willingness to manipulate our environments, human population has expanded in number unprecedented for a species of such large creatures. In the last few hundred years, the number of humans has grown from less than half a billion to 1 billion in the early 1800s, 2 billion in 1930, and 5.9 billion in 1998 (Fig. 5). The population is projected to increase to as much as 7 or 8 billion in the year 2010.

Figure 17. Growth of the human population since the Agricultural Revolution.

Human impact on the Earth's resources and environment is great, and it is proportional to the number of people. Like all other species, humans compete for and use essential resources; air, water, food and space. The negative environmental impacts of the Industrial Revolution include air and water polution, soil erosion, the concentration of human wastes, and the spread of disease. As a result, environmental awareness and legislation have increased in many nations, especially in the last few decades of the 20th century.

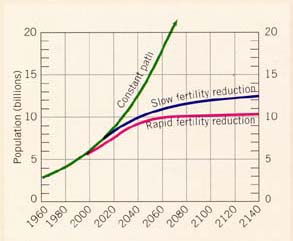

As global population has surpassed 6 billion, concern is mounting over how many more people will be added in the future. Human population growth has been nearly impossible to predict accurately (Fig. 18) because it depends on a bewildering array of variables, from advances in agriculture, sanitation, and medicine to the influences of culture, religion, and medical practices. The rate of human population increase has varied throughout human history, but its most striking feature is an accelerated increase in the last few hundred years. One of the greatest shortcomings of the human species is its unwillingness to face the consequences of accelerating population growth.

Figure 18. Example of human population growth prediction. The green line shows the predicted number of humans using an unchanged fertility (human fertility as in 1998). The blue and red lines show predictions assuming a decrease in human fertility (birth control, China-type number of children laws, etc.).

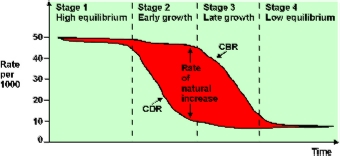

The population explosion as observed in the last few hundred years can be explained by the Demographic Transition Theory, which is an important - if not unanimously accepted - theory in demographic studies. It describes the process of change of high birth rates and death rates to low birth and death rates as related to economic development. The theory can be described in a diagram (Fig. 19) showing two curves over time; one for crude birth rate (CBR) and one for crude death rate (CDR). CBR and CDR are measured as the number of live births per 1000 population and the number of deaths per 1000 population. The demographic transition theory was developed based on the historical experience of western industrial countries in Europe. The demographic transition theory holds that in the stage before the scientific revolution, life expectancy was low owing to poor nutrition, poor medical care, unreliable food supply, and poor sanitation. The high death rate is matched by a high birth rate, keeping the growth rate fairly low. During the second stage, as innovations began to occur, the death rate dropped because of medical advances, a more reliable food supply, better sanitation, etc. The birth rate, however, remained high. During the third stage, the birth rate falls for a number of reasons. For example, in an increasingly industrial economy children become a "cost" rather than a source of cheap labor as in a farming economy, care for the elderly, longer eduction, etc.

Figure 19. Diagram illustration ofthe four stages of the Demographic Transition Theory (CDR = crude death rate, CBR = crude birth rate).

Finally, in the fourth stage of the demographic transition, the death rate and birth rate are once again stable, but both are at a considerably lower level than they were before the scientific revolution. Some of the advanced industrial economies of Europe, as well as the USA, Japan, and a few other wealthy countries where a low population growth has been achieved, are frequently given as examples of societies at this stage.

As mentioned earlier, the demographic transition theory was developed based on historical experience of Europe. There is some disagreement about its transferability to contemporary less developed countries:

- Europe took several centuries to go through the transition, the Third World is experiencing it much more rapidly.

- Europe experienced rapid economic growth as it went through the transition, an experience not mirrored in most of the Third World.

- European countries had a population "safety valve", namely colonialism, through which the surplus European population was able to emigrate to colonized nations.

- Most of the Third World entered the transition with much higher population density than that found in early modern Europe.

Thus, there are no garanties that the demographic transition will happen in the same way or to the same extend in the Third World as it did in Europe and other industrialized regions.

10.1. Resources and sustainable development

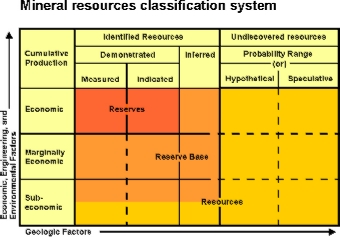

Does the Earth have some finite "carrying capacity", some threshold number of people beyond which it cannot sustain the human population with clean air, clean water, and adequate nourishment? To answer this question, men need to consider not only the number of people but also the quatity of resources necessary for their survival. A resource is anything we get from our environment that meets our needs and wants. Some essential resources, such as air, water, and edible biomass, are available directly from the environment. Other resources are available only because we have developed technologies for exploiting them. Figure 20 shows a mineral resources classification diagram. The most important part of the mineral endowment consist of reserves, material that has been identified geologically and that can be extracted at a profit at the present time. The reserve base includes reserves as well as already identified material of lower geological quality that might be extractable in the future, depending on economic or engineering factors. Resources include the reserve base plus any undiscovered deposits, regardless of economic or engineering factors.

Fig. 20. Mineral resource classification system of the US Bureau of Mines and US Geological Survey.

Our impending mineral supply crisis can be averted only by converting resources to reserves. But this must now be done in the context of environmental constraints. Environmental costs impact the economic axis of Figure 20, thereby controlling the overall profitability of extration. Besides the mineral resources classification system shown in Figure 20, resources are also classified according to their degree of renewability (Fig. 21).

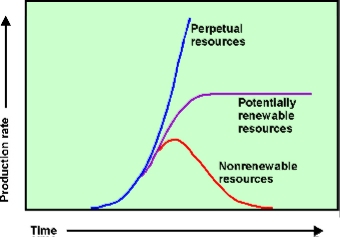

Figure 21. As demand for a resource increases, more of it is produced. For nonrenewable resources, production cannot increase forever, because ultimately the resource will be exhausted. Potentially renewable resources can provide lasting supplies if the rate of production is similar to the rate of renewal. Only for perpetual resources is unlimited increase in production possible.

Nonrenewable resources, such as fossil fuel and metals, are finite and exhaustible. Because they are produced after millions of years under specific geological conditions, they cannot be replenished on the scale of human lifetimes. Some nonrenewable resources, such as metals, can be recycled in order to prolong the time to exhaustion. Nonrenewable resources become economically depleted when so much, typically 80 percent of the resource, is exploited that the remainder is too expensive to find, extract, and process. Potentially renewable resources can be depleted in the short term by rapid consumption and pollution, but in the long term they usually can be replaced by natural processes.

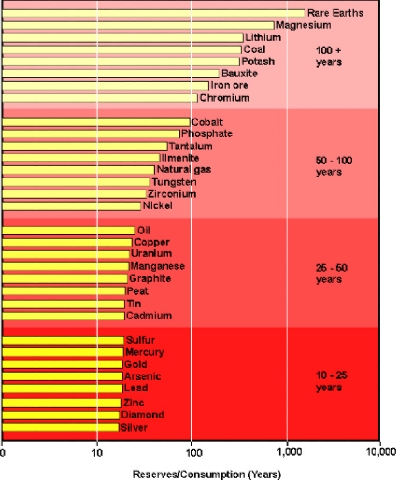

Figure 22. Adequacy of world mineral reserves illustrated as the ratio between reserves and annual production for 1992.

The highest rate at which a potentially renewable resource can be used, without decreasing its potential for renewable, is its sustainable yield. If the sustainable yield is exceeded, the resource can be exhausted. Soil formation, for example, occurs at rates of about 2 to 3 cm per thousend years, making it a potentially renewable resource. Unwise farming practices, however, can cause soil loss of 6 to 8 cm per decade. In some parts of the world, all soil has been removed and so is essentially nonrenewable. Perpetual resources are those that are inexhaustible on time scale of decades to centuries. Examples include solar energy, which has fueled numerous reactions and processes on Earth for its entire history, heat energy from the interior of the Earth, and energy generated by Earth's surface phenomena such as wind and water flowing downhill.

Figure 22 shows the reserves for a number of nonrenewable resources and their time before depletion, estimated using values for production and consumption rates of 1992. With world population and the standard of living increasing rapidly, the time periods obtained using the 1992 consumption rates are almost certainly overly optimistic, however, possibly by a factor of two to three. In other words, we have only a decade or so before reserves for many mineral commodities will be exhausted.

This puts us in a difficult position. On the one hand, we need to find minerals and produce them, and on the other, we want to keep the environment as clean and undisturbed as possible. Mineral wastes are among our worst legacies from earlier times and we will spend many decades cleaning them up. However, we should not let this clean-up effort cause us to forget the need to continue producing minerals. Modern society is based on minerals and we cannot recycle enough of them to supply a growing demand.

10.2. Pollution, Wastes, and Environmental Impact

Pollution is the contamination of a substance with another, undesirable, material. Environmental pollution results when a pollutant degrades the quality of the environment. Common pollutants in urban areas are carbon dioxide (CO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx), all of which are created by combustion of fossil fuels. Wastes are unwanted by-products and residues left from the use or production of a resource. Modern humans in industrialized societies have high population densities and technologies that enable them to concentrate large amounts of waste, much of which is toxic and infectious.

Scientists have developed a simple model of environmental degradation and pollution to assess the environmental impact of human populations. In this model, the extent of the environmental impact depends on three variables: (1) population, (2) per capita consumption of resources, and (3) the amount of environmental degradation and pollution per unit of resource used:

-

Environmental Impact = 1 x 2 x 3.

According to this model, three types of environmental degradation can occur. The first people overpopulation, occurs when a large group of people has insufficient resources. Although the group's per capita consumption of resources is low, the per capita amount of environmental degradation is high because this group must scavenge all available resources in order to survive. In parts of northern and western Africa, for example, large areas of land have been denuded of most vegetation and famine has occurred repeatedly in the 20th century. The second type of degradation, consumption overpopulation, occurs when a small number of people use resources at such a high rate per person that they cause very high levels of resource depletion and pollution. Ranking first among modern examples is the United States, which has less than 5 percent of the world's population but consumes more than 33 percent of nonrenewable energy and mineral resources and produces more than 33 percent of the world's pollution. In contrast, China has about 21 percent of the world's people, but causes less than one-tenth the environmental damage of the United States. The third type of environmental degradation, pollution overpopulation, occurs when a small or a large number of people use technologies that are grossly polluting. In this case, the amount of pollution produced per unit of resource used is so high that extreme environmental degradation occurs. Industrialized countries in eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union have amassed a legacy of environmental pollution.

10.3. Natural Disasters, Hazards, and Risks

Natural disasters are sudden and destructive environmental changes that happen as a result of long-term geological processes but appear to occur without notice. Earthquakes, for example, are the result of hundreds or thousends of years of build-up of geological strain, but the "breaking" point occurs relatively suddenly. A geological hazard is a natural phenomenon or process with the potential for disaster. Rocks perched at the top of a steep hill constitute a hazard. A destructive rock avalanche is a disaster. Like human-made disasters such as oil spills and air pollution, natural disasters can pollute the environment, for example, the seeping of radon from the ground and degassing of volcanoes. Volcanic eruptions and earthquakes are natural disasters are caused almost entirely by the interior processes that move the Earth's tectonic plates. Floods and landslides, in contrast, are natural disasters that can be worsened markedly by human activities. Removing vegetation from hillslopes, for example, can increase the runoff of rainwater and thereby increase flooding in streams. Removing vegetation also destroyes roots, which anchor the soil on slopes. landslides occur when loosened soil and other debris slip suddely downhill. As human population increases, so does the hazard associated with natural disasters. Mitigating natural disasters requires increased effort from geoscientists to understand natural phenomena and their causes.